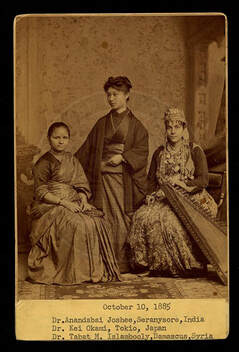

c. 1885. (Left to Right) Anandibai Joshee of India, Kei Okami of Japan, and Sabat Islambooly of Syria. At first glance, this photo might appear like another yellowed, grainy relic of the past, but contained in it are the faces of change. Since humanity’s inception, the practice of medicine has endured. Around the world, men and women took it upon themselves to learn more about the human body. Through painful – and often fatal – trials and experiments, mankind slowly garnered a deeper understanding of life and the microcosms that affect humans. While both men and women sought to uncover the mysteries of the human body and contributed equally to the reservoir of knowledge from which humanity could draw, it was men who were given the go-ahead to specialize in certain fields and practice professionally. There have been numerous identified groups throughout the ages regarded as keepers of medical knowledge. In the West, the charter for the Company of Barber-Surgeons was granted by the infamous Henry VIII of England, allowing doctors – male doctors – to specialize in medicine. Just because women were barred from entering the guild, however, didn’t stop their pursuit of knowledge. Women made great strides in nursing, midwifery, and pharmaceuticals around the world. In the late 1800s, women began pushing back, demanding with stubborn vehemence to be admitted into schools of medicine. Because the prevailing school of thought at the time for most nations was that women should be keepers of the house, demure and stewards of morality, the surge of female determination that rose against the conservative majority was greatly unwelcomed. While many women backed down with disappointment, there were those who did not. Of that small collection of determined individuals are the three women photographed above. All three women completed their medical studies; each became the first woman physician in her respective country to hold a professional degree in Western medicine. Dr. Anandibai Gopalrao Joshi, born in 1865, was encouraged by her husband from an early age. Married at the tender age of nine, Anandibai found an advocate in her vastly older husband who was surprisingly progressive and supported women’s education. Despite being poor in health, Anandibai’s husband encouraged her to set sail for America to pursue higher education. Anandibai applied to the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and was accepted at the age of 19. Although her health failed her often, Anandibai graduated in March of 1886. Later that year, she returned to India where she was appointed as the physician-in-charge of the female ward of the local hospital. Dr. Kei Okami of Japan, like Anandibai, was also a student of the Pennsylvanian Woman’s Medical College. After marrying at the age of 25, she and her husband traveled to America where Kei enrolled in the college. She graduated in 1889, becoming the first Japanese woman to attain a medical degree from a Western university. Upon returning to Japan, she began work at a hospital in Tokyo. Throughout her life, she opened several clinics where she taught nurses and tended to the sick. Less is known about the third medical professional in the above photo, Dr. Sabat Islambooly (Islambouli). Born circa 1867, though that date has not yet been confirmed, Sabat was also a graduate of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania becoming the first woman from Syria to be licensed. Shortly after graduating, she returned to Damascus before moving to Cairo, Egypt in 1919. After that, there are few records of her life. All that is known is that she died in 1941. The lives of these women might seem distant and inconsequential, but they were the progressives of their time. They were the determined, the fierce, the dedicated. They were harbingers of change.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Kara WilsonOwner/Editor of Emerging Ink Solutions, avid YA/NA author, adamant supporter of the Oxford Comma, anime and music enthusiast. Archives

February 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed