|

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve shared with people that I’m an author/editor and they’ve responded with, “Oh! I’ve always wanted to write a book!” or “I’ve been thinking about writing a book!” or “I started to write a book a few years ago but never finished it…” As they enthusiastically launch into how they were writing a memoir, I simply present a polite smile and nod. Not because I’m uninterested or am a mean-spirited person, mind you. But because such responses are nearly constant. It’s become a running joke between myself and my husband.

The best advice I can impart wannabe writers is this: develop self-discipline. Sit down and write. Force yourself to write. Every day. Set a schedule, make it a part of your routine, and do it. Don’t make excuses. Self-discipline separates writers from wannabe authors. It was American Robert Greene who said, “Mastery is not a function of genius or talent; it is a function of time and intense focus applied to a particular field or knowledge.” Just like anything else in life, if you want to be good at something, you must practice it. Even if you’ve had a stressful day or are exhausted, if it is your desire to be an accomplished author, open that MS Word document and write! Even when I’m exhausted from a day’s activities, I open my work in progress. My mind might be unable to produce content at that moment, but I can most definitely reread what I’ve written, edit, and place myself in that creative mindset. Don’t talk yourself out of it! I also recommend that you read, read, read! How can you write if you do not like to read? How can you connect with readers if you don’t continuously explore how others do it? Expose yourself to a variety of genres and take note of how authors convey information. If you passionately read YA fiction, delve into a memoir. If you usually select mystery-thrillers, pick up a steamy romance novel or a historical fiction book. The more you expose yourself to the incredibly vast world of writing, the deeper your well of experience and comprehension grows. It's just that simple—and difficult.

0 Comments

Yes! This is especially important if you have written many books or intend to write more than one. However, even if you have just a single creative work, it is vital that you have a digital presence. Having a single hub of activity where you can send people interested in reading your book is integral to an author’s success.

Suppose you’re doing a book signing or have a table at a book festival and a potential reader stops by. They’re interested in your book but are supposed to meet a friend shortly, or they don’t carry cash on their person, or perhaps they’re too shy to interact further. If you give them some sort of takeaway (a business card, a postcard-sized promotional, a flyer, etc.) pointing them to your author website, they can make a purchase when it suits them. Creating an author website doesn’t have to be an intimidating process! There are several reputable website hosting platforms that make building a website easy! Emerging Ink Solutions recommends the following: Weebly WordPress SquareSpace Site123 Wix Hostinger Website Builder Remember, when building a website, be creative and work hard to make it appear professional. Users/readers can immediately discern if a website was constructed by a novice. Use stock photography to spruce up landing pages. There are countless stock photography websites. Here are the ones we recommend: Shutterstock 123rf Pexels Unsplash Adobe Ensure your website is concise, professional, and error-free. Read and reread posted content for mistakes. Make sure you direct readers to the digital platform where your book can be purchased. For instance, if your book is available through Amazon KDP, link it to your website. You can do this by simply going to Amazon.com and searching for your book. The URL on your product’s page is what you would link on your website. Author websites are integral to the development of self-published authors. Of course, each of the above-mentioned website hosting platforms has a learning curve, but they are intended for users with little to no website design experience. You can do it!  c. 1615. Hasekura’s portrait by French Baraoque painter Claude Deruet. Look at this dapper gentleman, at his neatly pressed wardrobe, at his swords jauntily positioned at his hip; look at the casualness of his stance. Now, study the painting behind him, the dog at his feet, the curtains and flooring. Take notice of the striking differences in light and shadow, the rich colors between the foreground and background. The painting itself does not appear to be of Asian origin, does it? Are you confused? This painting has all the elements of a Baroque painting, a European cultural movement that swept the region in the 17 and 18th centuries. Yes, that’s right – European. This portrait is of Hasekura Tsunenaga (支倉六右衛門常長), a Japanese samurai and retainer of a regional ruler of Japan who founded the modern-day city of Sendai, Japan. At a time when the nation of Japan was beginning its persecution and suppression of Christianity within its borders, Hasekura ventured to Europe as head of the Keichou Embassy. Subsequently, he became the first Japanese ambassador in the Americas and Spain. With the encouragement of famous Spanish explorer Sebastian Vizcaino and the go-ahead from both the shogun of Japan and the regional ruler of Sendai, a galleon – a large, Spanish ship – was constructed. It set sail for Spain in October 1613. In addition to taking Spanish explorer Vizcaino back home, Hasekura’s objective was to discuss trade relations with Spain and Rome. In January 1614, the ship arrived in Acapulco, Mexico for a brief reprieve. Upon leaving for Spain in June, Hasekura took only half of his crew; those left in Mexico were instructed to continue trading. Hasekura, now traveling with a fleet of other merchant ships en route to Spain, arrived in October 1614, exactly a year after leaving Japan. The samurai was greeted by carriages, accommodations, and wide-eyed onlookers. Hasekura met with King Philip III in Madrid that following January. He remitted to the King a letter from his lord, the regional ruler of Sendai, and offered a treaty upon which King Philip III responded that he would try his best to accommodate the Japanese’s requests. Thereafter, Hasekura traveled to Italy to meet with Pope Paul V in Rome. He gave the Pope two gilded letters (one in Japanese and the other in Latin) which contained requests for a trade treaty between Mexico and Japan as well the dispatchment of Catholic missionaries to Japan. The Pope readily agreed to the latter of the two requests but could make no decision regarding trade as that was for the King of Spain to decide. Hasekura returned to Spain where King Philip III immediately declined to sign the trade agreement, stating that the Japanese Embassy didn’t appear to be official as it was the eastern nation’s ruler Tokugawa Ieyasu who, in just the previous years, had begun expelling missionaries from Japan and persecuting all those who practiced the Christian faith. By the time Hasekura returned to Japan, the nation had greatly changed. In the short amount of time Hasekura had been gone, the extreme persecution of Christians had been carried out and the nation was on its way to complete isolation which it would continue until the mid-1800s. Hasekura’s return was not joyous nor triumphant. Although he brought back goods and products from the West, he had failed to obtain a trade treaty from Spain. He reported his travels to the lord of Sendai, presenting him gifts from the esteemed rulers he had met as well as goods he had collected. Overall, Hasekura’s adventure was a failure. After several years of travel and careful diplomatic meetings, he brought back nothing for his country. The Japanese emissary himself, however, received many personal gifts during his travels. He was named a Roman Noble and a Roman Citizen. In Havana, Cuba where his ship had stopped briefly, a bronze statue was erected of him. Hasekura was baptized by King Philip III’s personal chaplain and made godchild of the de facto ruler of Spain, the Duke of Lerma. How’s that for creating a name for himself?

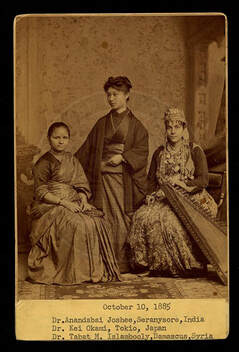

c. 1885. (Left to Right) Anandibai Joshee of India, Kei Okami of Japan, and Sabat Islambooly of Syria. At first glance, this photo might appear like another yellowed, grainy relic of the past, but contained in it are the faces of change. Since humanity’s inception, the practice of medicine has endured. Around the world, men and women took it upon themselves to learn more about the human body. Through painful – and often fatal – trials and experiments, mankind slowly garnered a deeper understanding of life and the microcosms that affect humans. While both men and women sought to uncover the mysteries of the human body and contributed equally to the reservoir of knowledge from which humanity could draw, it was men who were given the go-ahead to specialize in certain fields and practice professionally. There have been numerous identified groups throughout the ages regarded as keepers of medical knowledge. In the West, the charter for the Company of Barber-Surgeons was granted by the infamous Henry VIII of England, allowing doctors – male doctors – to specialize in medicine. Just because women were barred from entering the guild, however, didn’t stop their pursuit of knowledge. Women made great strides in nursing, midwifery, and pharmaceuticals around the world. In the late 1800s, women began pushing back, demanding with stubborn vehemence to be admitted into schools of medicine. Because the prevailing school of thought at the time for most nations was that women should be keepers of the house, demure and stewards of morality, the surge of female determination that rose against the conservative majority was greatly unwelcomed. While many women backed down with disappointment, there were those who did not. Of that small collection of determined individuals are the three women photographed above. All three women completed their medical studies; each became the first woman physician in her respective country to hold a professional degree in Western medicine. Dr. Anandibai Gopalrao Joshi, born in 1865, was encouraged by her husband from an early age. Married at the tender age of nine, Anandibai found an advocate in her vastly older husband who was surprisingly progressive and supported women’s education. Despite being poor in health, Anandibai’s husband encouraged her to set sail for America to pursue higher education. Anandibai applied to the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and was accepted at the age of 19. Although her health failed her often, Anandibai graduated in March of 1886. Later that year, she returned to India where she was appointed as the physician-in-charge of the female ward of the local hospital. Dr. Kei Okami of Japan, like Anandibai, was also a student of the Pennsylvanian Woman’s Medical College. After marrying at the age of 25, she and her husband traveled to America where Kei enrolled in the college. She graduated in 1889, becoming the first Japanese woman to attain a medical degree from a Western university. Upon returning to Japan, she began work at a hospital in Tokyo. Throughout her life, she opened several clinics where she taught nurses and tended to the sick. Less is known about the third medical professional in the above photo, Dr. Sabat Islambooly (Islambouli). Born circa 1867, though that date has not yet been confirmed, Sabat was also a graduate of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania becoming the first woman from Syria to be licensed. Shortly after graduating, she returned to Damascus before moving to Cairo, Egypt in 1919. After that, there are few records of her life. All that is known is that she died in 1941. The lives of these women might seem distant and inconsequential, but they were the progressives of their time. They were the determined, the fierce, the dedicated. They were harbingers of change.

|

Kara WilsonOwner/Editor of Emerging Ink Solutions, avid YA/NA author, adamant supporter of the Oxford Comma, anime and music enthusiast. Archives

February 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed